How to Craft a Narrative Arc

While crafting a strong narrative arc may seem daunting, doing this is usually pretty quick and easy—it just requires some planning and thought. First, every story has a beginning, middle, and end, with the middle typically taking up a longer period of time than the beginning or the end, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1—The parts of a story

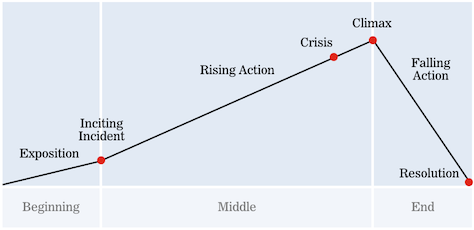

Then, every story has an arc that looks a bit like that in Figure 2.

Figure 2—A story arc

While the X-axis in Figure 2 represents time, the Y-axis represents the action. In other words, what Figure 2 illustrates is simply this: stories build in excitement and the pace of their action increases over time until they hit a high point, then wind down before they end. When they don’t wind down and instead end while the action is still rising or at a peak, we call the story a cliffhanger.

Every narrative arc has key points, and while an avant garde story might meander and break the narrative-arc model whenever possible, traditional stories have key plot sections and points that map nicely onto this arc, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3—Action on a story arc

Let’s break down each key part and point in the narrative arc.

Exposition

This is how all stories begin and get set up: they introduce the world, the characters, and the genre, theme, or general feeling. Usually, in the exposition, all is well in the world. Why? So something can go wrong later—the inciting incident. One example we like to use is Back to the Future, which has a pretty simple exposition: Marty McFly is a guy who lives in Hill Valley—any suburb USA. Doc is a mad scientist and has a time machine. Cool!

Inciting Incident

“The inciting incident is a moment where something goes wrong in the world of the story. At that point, the protagonist of the story goes on a type of journey to right that wrong, and we spend the rest of the story seeing how it all pans out.”

The inciting incident is a moment where something goes wrong in the world of the story. At that point, the protagonist of the story goes on a type of journey to right that wrong, and we spend the rest of the story seeing how it all pans out. In Back to the Future, the excitement of a time machine doesn’t last long; a gang of misfits shoot Doc in a parking lot. Not good. In an attempt to escape, Marty ends up driving the time machine to 1955, then finds out that he doesn’t have enough fuel to get home. Really not good!

Rising Action

Like a good essay, a good story builds over time. Rather than making the most exciting thing happen right after the inciting incident, with the rest of the story remaining flat, storytellers build anticipation and excitement as the plot gets more and more interesting. During the rising action of any good story, there is also some friction to keep the audience engaged. Without friction, endings come too easily, and the audience is unconvinced or bored or both. In Back to the Future, Marty sets out to find 1955 Doc, and they try to get Marty home.

Crisis

The story culminates at the point of maximum friction—what we call the moment of crisis. It’s the point of no return. Something really bad happens, and the story either has to right itself or end. In Back to the Future, this is the point at which Marty is close to getting home, but starts to disappear. He has to right the wrong that he’s introduced in the space-time continuum by getting his parents together. Otherwise, he’ll never be born in the altered future.

Climax

“The climax occurs at the top of the story arc. It’s the most exciting part of the story and the point at which something cool happens that makes us realize that all might be well with the world again—but not quite yet, because the story still has to reach its end.”

Just as it sounds, the climax occurs at the top of the story arc. It’s the most exciting part of the story and the point at which something cool happens that makes us realize that all might be well with the world again—but not quite yet, because the story still has to reach its end. Often in stories—especially in movies—the crisis involves a kiss between two characters, as in Back to the Future. Marty’s parents kiss; they dance; so now it just might be possible to get home. But wait! There’s more! There’s a clock tower and lightning. Will Marty be able to get home?

Denouement, or Falling Action

This is how the story ends. Because you usually can’t just end at the climax. (Remember, if you do, it’s a cliffhanger.) The action starts slowing down in pace. Sometimes, as in Back to the Future, you literally see falling action—in this case, from the top of a clock tower and leading to Marty getting home. It’s how everything in the story gets wrapped up.

Resolution

Quite literally, this is the end. Often, stories end with the protagonist coming home after a long journey, as in Back to the Future. Marty McFly arrives home in present-day Hill Valley. Sometimes this resolution sparks an entirely new narrative, or sequel, which brings up the topic of serial narratives. In the world of user experience and product design, designing for serial narratives is a great way to tackle long-term engagements and repeat use cases. Sadly, serial mechanics are too complex a topic to cover within the scope of this article. We know, we know! Cliffhanger!